By Frank Stricker

April 12, 2024

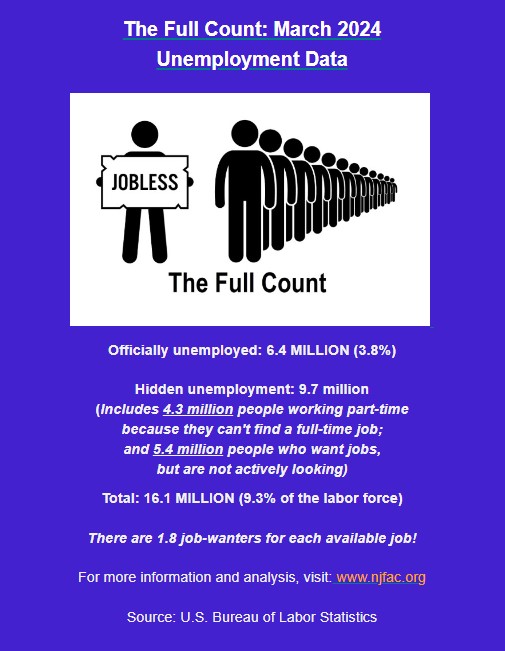

In the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ (BLS) Employment Situation–March 2024, the unemployment rate was 3.8%. It has been under 4% for two years and that is a positive. But if we add to the unemployment numbers involuntary part-timers (people who want full-time work) and job hunters who are not currently looking for but want a job—bystanders we might call them—we get an unemployment rate of 9.3%. (See the Full Count). The BLS’s own amplified enumeration of real unemployment was 7.3%.

The official unemployment rate for disabled people was 8.6% and for African-Americans 6.4%. The rate for teens was 11% and for African-American teens it was an incredible 20.1%. And if these categories underestimate unemployment as much as the overall official rate, real unemployment rates for these groups are horrendous. And if you are wondering why “full employment”—4% or less—has not propelled real wage growth, it is in part because we do not have real full employment.

Bomb-Throwers

Recently several commentators have been throwing bombs at the government’s statistics. A Bloomberg analyst named John Authers called his article, “Might as Well Throw Jobs Data Against the Wall” (January 5, 2024). A Forbes writer named Derek Saul wondered: “Could 300,000 Job Openings Be Fake? Here’s Why Goldman Thinks They Might Be” (May 18, 2023). Tyler Durden at Zero Hedge (“Philadelphia Fed Admits U.S. Payrolls Overstated by at Least 800,00,” March 29, 2024) claims that the Biden administration has been cooking the books on job totals from the employer payroll survey.

I have not found much that has convinced me to believe these charges or that we should throw out the government’s numbers and just start guessing. It is true that response rates in government surveys have declined since COVID, but most commentators do not seem to be concerned about that issue.[1]

Tyler’s Best Point

Giving credit where it is due, Tyler Durden noted that for the year from February 2023 through February 2024, the total number of added full-time jobs in this booming economy was just 300,000. That is, almost no added full-time jobs. Most job growth was in the ranks of part-time workers. The BLS divides part-timers into two groups. The smaller group includes involuntary or economic part-timers who want full-time jobs but cannot find them. Also, people who have had their hours cut. In March 2023 there were 4,091,000 economic part-timers; in March 2024, 4,308,000—too many, but these are not the bulk of the part-time population. Most people are part-time for “non-economic reasons,” including that they could not or did not want to work full-time, for example, because of school attendance, lack of reliable child-care alternatives, or because they had retired but decided they wanted to work a little. The whole group of willing part-timers increased by 1,486,000–from 21,416,000 in March 2023 to 22,902,000 in March 2024. We assume that these people are part-time not because the economy is failing, but because they do not want full-time work; or they cannot for other reasons, including the absence of a strong social support network.

Immigrants and Oldsters

In the last twelve months the number of employed native-born workers in the 16-and-over population fell by 651,000. The number of foreign-born employed workers increased by 1,266,000. Are immigrants pushing native-born workers out of the labor force? Not really. The total number of native-born adults in the whole population–workers and non-workers—has declined by a million since last March. The number of foreign-born people 16 and over increased by two and a half million. And this must be a long-term trend. The U.S.-born population is older, and its members die more often than the younger immigrant population. BTW, most of the baby boomers are out of the labor force–deceased or retired. Those born in the last year of the boom, 1960, are now about 64.

In terms of wages, a large supply of immigrant workers has both negative and positive effects. Lots of needy workers must have a depressive effect on wage growth and that is harmful. On the other hand, to the degree that wage movements affect inflation rates, a bulging work force provides a partial check on inflationary forces and that means less pressure on the Federal Reserve to engineer a recession. But it does not mean no inflation. Annual price increases of 4 to 5% are significant. After factoring out the impact of rising prices and leaving only changes in the purchasing power of a worker’s paycheck, real wage increases are almost non-existent. For rank-and-file workers in the private sector, the real hourly wage over the past twelve months increased by a non-whopping 0.7%–less than 1%. And this was not an exceptional year. Compare real wage levels in March of 2017 and March of 2024. The real hourly wage of average production and nonsupervisory workers last month was higher than their wage in 2017, but only by 5.5%. That means average increases of less than 1% a year. Rich people did much better than this and partly because average workers did not get more in their paychecks.

Frank Stricker is on the board of the National Jobs for All Network and writes for NJFAN and Dollars and Sense. In 2020 he published a history called American Unemployment: Past, Present, and Future (2020). He taught History and Labor Studies at California State University, Dominguez Hills, for 37 years.