By Frank Stricker

May 22, 2024

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), the official unemployment rate stayed below 4% for the 27th month in a row. It’s a good record but not unique. Unemployment was under 4% for all but two months from May 2018 through February 2020. And as war spending helped to boom the economy in the late 1960s, official unemployment remained below 4% from February 1966 through January 1970 except for two months.

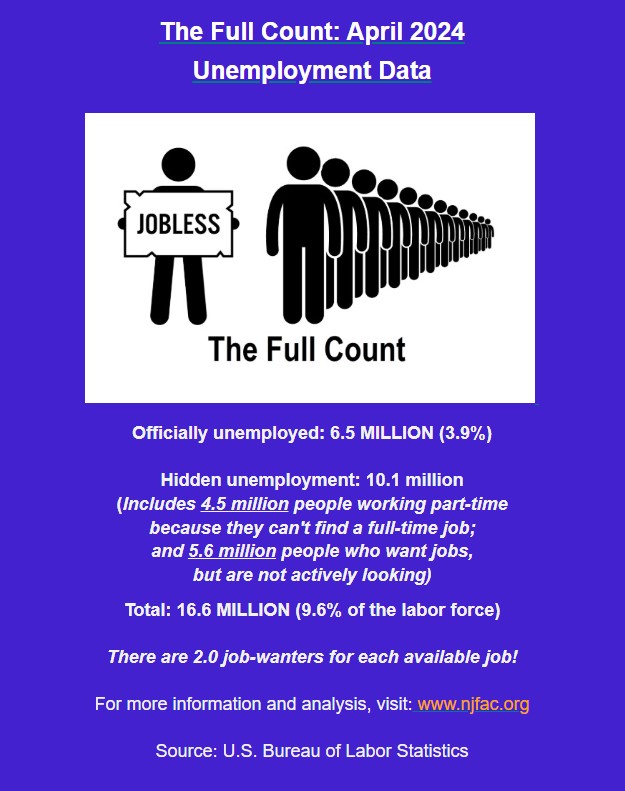

So under 4% is good although not unique. And it is not real full employment. That is clear if we look at the numbers for special groups of workers and if we examine hidden unemployment (see paragraph 4) for the whole labor force. Negative examples of the former include a 6.3% unemployment rate for disabled workers and an 18.2% rate for black teens. Including hidden unemployment, the unemployment rate for the whole population was 9.6%, 2 ½ times the official rate. What must real unemployment rates be for black teens and disabled workers?

It does not take a lot of imagination to think that there is much discouragement among some groups not only about finding work but finding decent pay. I don’t have official discouragement numbers for specific groups. For the whole labor force, by official count there were just 362,000 discouraged job seekers in April. That is, 362,000 people who wanted jobs but believed there were none for them and so did not search in the past four weeks. I think the BLS often underestimates the number of discouraged workers. Here is an extreme example to make the point. For October 2009, during the Great Recession, when the Bureau said there were 15.7 million unemployed and 10.2% unemployment, it found only 808,000 discouraged workers. That does not seem credible.

The National Jobs for All Network’s estimate of joblessness for April of 2024 adds two categories of hidden unemployment. It includes more people and a less rosy picture than the BLS report. We try to make it simple: we add part-timers who want full-time work and don’t have it because their hours have been cut or they can’t locate full-time jobs. And we add job-wanters not currently searching. Our unemployment rate is 9.6%, obviously not full employment.

Signs of Slowing?

Some commentators see signs that job growth may be slowing:

1. In the survey of employers, job additions slowed to 175,000 in April. That is one of the lowest totals in the last 12 months. The average addition for 12 months was 240,000. There were other slow months, and it is impossible to tell whether 175,000 is the start of something worse.

2. Observers have noticed that job openings through March were down a bit to 8.5 million. But a drop from the high vacancy levels that followed the massive pandemic job decline was to be expected. And the level of 8.5 million openings is not so low; it’s higher than any month between 2002 and 2020. We don’t have to cheer, but 8.5 is not unusually low.

3. Last week, initial unemployment insurance claims rose by 22,000 individuals to 231,000. But the four-week average is not yet particularly high, and the numbers were higher last June, July, and August and then fell. This latest increase is not yet a trend.

While lower interest rates might catalyze more job creation and fewer people signing up for unemployment benefits, they won’t solve the continuing problem of high levels of hidden unemployment, nor the fact that unemployment hits some groups much harder than others. Nor will it do enough to address the fact that millions of workers get lousy compensation. On the wage front there is a bit of encouraging news in a report for the Economic Policy Institute by Elise Gould and Katherine DeCourcy: Fastest Wage Growth over the Last Four Years Among Historically Disadvantaged Groups (March 21, 2024). The authors show that real wages for low-wage workers advanced by 12.1% over 2019-2023, much faster than for higher-wage groups. The causes, the authors argue, were higher minimum wage laws and tight labor markets. Clearly, we need more of both. But such methods won’t bring really tight labor markets and it is hard to call the current situation tight when real unemployment is 9.6%.

How about direct government creation of millions of good jobs? By conventional standards workers today inhabit a very good labor market. But tens of millions of workers and their families are poor and they are going to stay that way if we rely only on attainable heights for minimum wages and the current kind of tight labor markets. For one thing, most state and local minimum wage levels are very low. A while back, famously progressive California raised its general minimum from $15 to a whopping $16. For 2000 hours of work a year that’s a raise from $30,000 of pre-deduction annual income to $32,000 pre-deduction annual income. That’s poverty for many households and I don’t care if the Census Bureau says otherwise.

Frank Stricker is on the board of the National Jobs for All Network and writes for NJFAN and Dollars and Sense. In 2020 he published a book called American Unemployment: Past, Present, and Future (2020). He taught History and Labor Studies at California State University, Dominguez Hills, for 37 years.