by Trudy Goldberg

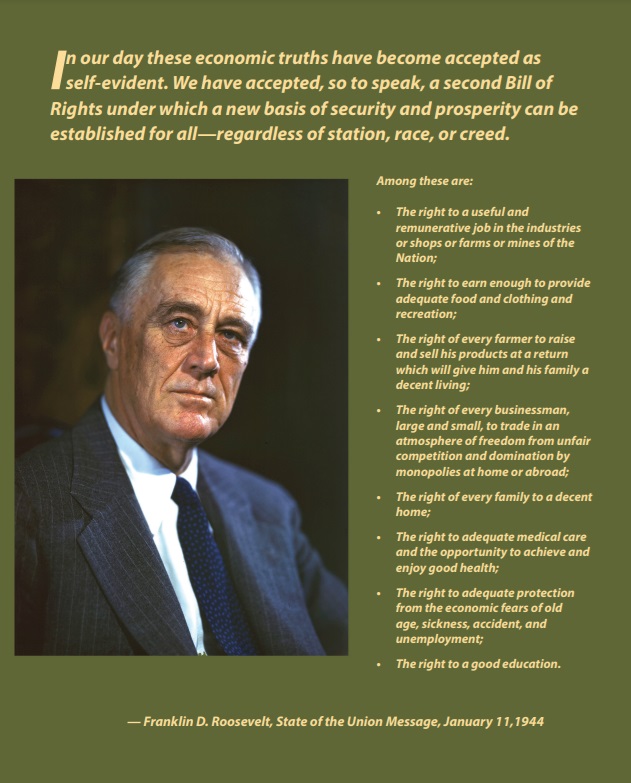

Chief among the sources of inspiration for the National Jobs for All Network is this ground-breaking proposal of Franklin Roosevelt–for a Second or Economic Bill of Rights.

In his 1945 State of the Union Address–when he repeated this call for a Second Bill of Rights–FDR referred to the guarantee of employment as “the most fundamental, and one on which the fulfillment of the others in large degree depends.” The Economic Bill of Rights, in asserting interdependence in the fulfillment of economic rights, implies that concerted action on the part of economic justice advocates would be mutually beneficial. The National Jobs for All Network strives for such concerted advocacy.

“An Economic Bill of Rights for the 21st Century,” a conference held at Columbia University in Fall 2013, was organized by chairs of the Columbia University Seminar on Full Employment, Social Welfare, andEuity who were also leaders of the National Jobs for All Network.[1] A paper prepared for that Conference by two of its organizers, Sheila D. Collins and myself, assessed the extent to which the economic rights proposed by President Roosevelt had been achieved. We concluded that even though the United States had become a much wealthier nation in the 69 years since FDR’s landmark proposal, none of the proposed economic rights had been achieved–despite notable progress on some of them. We were then still recovering from the Great Recession of 2008 in which we had lost some ground on economic rights.[2]

FDR’s Economic Bill of Rights was far-reaching, but with the passage of time, some new rights had arisen. One such right addresses the declining strength of the labor movement. Among the achievements of the New Deal was the legal establishment of collective bargaining rights. Perhaps because FDR felt collective bargaining rights had been secured through the National Labor Relations Act of 1935, it was not included among the economic rights he proposed. In view of the deep decline in union density since the 1950s and the fact that unionized workers earn higher wages and have more workplace benefits than non-union workers, we recommended the addition of The Right to Collective Bargaining. In making this recommendation, we called attention to repeated failures to enact federal legislation to protect collective bargaining rights. The latest attempt, the Protecting the Right to Organize Act, has stalled in Congress.

There is an important precedent for the addition of this right in Article 23 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights that pertains to the “right to work.” One of the four parts of Article 23 is “the right to form and to join trade unions for the protection of his (sic) interests.”

The most important addition to our proposed 21st century Economic Bill of Rights is The Right to a Healthful and Sustainable Environment. Though not an economic right, per se, it is really foundational. Without a sustainable environment, all the other rights are threatened. The fear of job loss is a formidable barrier to climate change mitigation, one that could be reduced by the guarantee of living-wage work. One means of delivering that right is the creation of government jobs that contribute to environmental sustainability or, like human service employment, use relatively few fossil fuels.

When Roosevelt took office in 1933, the United States faced not only an economic collapse, but the degradation of large parts of the natural environment—notably a Dust Bowl that rendered millions of acres unsuitable for farming with resultant uprooting of farm families no longer able to make a living. A naturalist from his youth, FDR immediately recognized the interconnection between the health of the natural ecosystem and the health of the economy, as well as the health of the body politic. There could be no economic security, he recognized, without a secure natural environment and no healthy democracy unless Americans saw themselves as related to each other through the interconnectedness of the natural world upon which they all depended. In his 1935 State of the Union message, Roosevelt spoke of environmental sustainability as requisite to the security of the American people. Out of this understanding he created three great programs to help restore both economic security and the natural resource base: the Civilian Conservation Corps, the Soil Conservation Service, and the Tennessee Valley Authority.

The environmental challenges we now face are exponentially larger than those faced in the 1930s, and their extent is not only regional or national–but planetary. Species extinction, climate change, the toxic poisoning of our air, water and food cry out for remedy. With his prescient concern for the environment–which he referred to as “the rightful heritage of all”—Roosevelt, were he president today, would, we felt, add The Right to a Healthful and Sustainable Environment to his Economic Bill of Rights.

Economist and economic justice advocate Mark Paul refers to the Economic Bill of Rights as a “north star of economic reform” that ties individual economic rights policies together. Paul’s book, The Ends of Freedom: Reclaiming America’s Lost Promise of Economic Rights (2023) offers a “comprehensive prescription…to address the problems of persistent economic insecurity in America.” The Ends of Freedom is reviewed in this issue.

Trudy Goldberg is Professor Emerita of Social Work and Social Policy at Adelp[hi University and Chair of NJFAN. She is the author of numerous popular and scholarly works on comparative welfare states focusing on the poverty of women, the New Deal, and the struggle for economic justice.

Download Franklin D. Roosevelt Economic Bill of Rights Graphic (PDF)