By Frank Stricker

January 21, 2025

The number of non-farm jobs, which comes from employer reports, grew by 256,000 in December. That was more than expected. For the whole of 2024, the total number of non-farm jobs increased by 2.2 million or 1.4%. That percentage doesn’t look so great. In the household survey, the number of employed persons increased by just a third of a percentage point from December of 2023 to December of 2024. If true, that is pathetic, but we are told that the household sample is much smaller and less reliable in this respect than the employers’ reports. So not to worry. (But that household sample is used to create our unemployment rates, so I will continue to worry.)

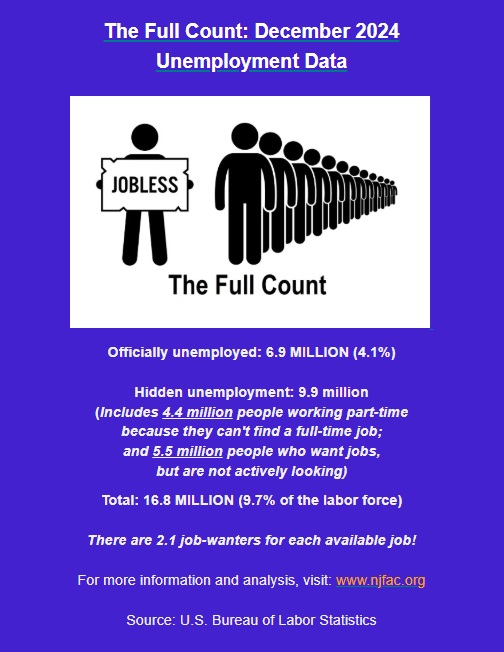

In December the unemployment rate fell by a tenth of a percent to 4.1%. The number of officially unemployed people fell from 7.1 million to 6.9 million. These numbers are moving in the right direction, but as our Full Count shows, the number of truly unemployed was huge and a more comprehensive unemployment rate was 9.7%. There is clearly much to be done for the whole work force, and it seems obvious that there should be special efforts for several groups in the labor force, including African Americans, teens, and disabled people.

Still, on the whole, can we say that job markets are moving in the right direction? Many commentators say yes. Unemployment is low according to mainstream guidelines. But it seems naïve to believe that we are at or near truly full employment–especially when we have very high unemployment for the three groups mentioned above, and when there are millions of discouraged workers who would like to work but have given up trying to find a job and so are not counted as unemployed. Some of these are included in the 5.5 million people in our Hidden Unemployment category as non-searching job-wanters. Adding that group to part-timers who want full-time work and cannot find it and the regular unemployed group, there are 17 million people who are unemployed or partly unemployed.

Other indicators are also negative. Job-openings rates have fallen in most months over the last year, although they perked up a little in October and November. Job-hiring rates fell in most months last year. Are the declines in job openings and hires a sign that we have finally gotten back to normal after the big recovery from pandemic job losses? Or are they a sign that the economy is entering a serious downturn?

The economy seems to be growing at steady if moderate rates. Growth in the real total output (GDP) of the U.S. economy was not bad in the second and third quarters last year at 3% and 3.1%. The recent prediction for the fourth quarter is 3%.

But economic growth of that level is not bringing relief to millions of workers. For example, real average hourly pay was up just 1% over the year for average workers. Should we be happy about that as some observers are? Well, it is not a decrease. But it’s not much. Dozens of millions of workers are getting lousy wages, before and after small increases.

One other indicator that is not so well known but possibly useful in judging the real temperature of the labor market is the worker quits rate. The theory is that more quits indicate that workers feel confident that they can leave their jobs and find better ones. Quits rates fell at first in the pandemic recession, but as heavy federal spending stimulated economic activity and job creation, they began to soar in the Spring of 2021. Remember the Great Resignation? Many people thought they could find better jobs. Quits reached their highest level on record in 2022. They have since fallen and are rather low at just over 2%. (They are measured as a percentage of total employment.) This may indicate a little more anxiety about finding jobs than quit rates over 3%. But the quit-rates were often under 3% in the past two years, and there wasn’t much talk of worsening labor markets.

Is it now really getting harder to find a job, especially a decent one? And will it get more difficult if inflation takes off, the Fed raises interest rates, and job growth slows? A bunch of different inflation rates were in the news in recent weeks, but one of them, the Consumer Price Index, rose by .3% in November and .4% in December. If that keeps up, it could mean an annual inflation rate of 4 to 5%. And that would lead to higher interest rates and less job creation.

Frank Stricker is on the board of the National Jobs for All Network and writes for NJFAN and Dollars and Sense. In 2020 he published a book called American Unemployment: Past, Present, and Future (2020). He taught History and Labor Studies at California State University, Dominguez Hills, for 37 years.